This work was developed as part of our artist residency in Pollen,

located in Monflanquin, initially scheduled from February 15th to May

15th, 2020, and thus during the lockdown. These two conditions

overlapped and created together a strange and uncertain space-time,

in terms of production, restitution and in the very direction of our

research. The residency continued remotely in our lockdown places,

and our common point of reference and departure, the space surrounding

Pollen from which we wanted to ponder on territory, landscape and garden

notions, by becoming inaccessible, ended up extended to the vast spaces

of internet and memories. Through their website, we visited gardening

and DIY stores, took images, objects, patterns, and walked through

gardens and landscapes as much in through our personal photographic

archives as through articles, online magazines, books or video games.

These "journey" took place in the absence of the body, parks and gardens

being closed and our movements limited. As the only accessible space,

the supermarket also becomes one of our resources, a place in which we

project the walking experience.

Gardens and landscapes deserve [...] to be considered in their "in

situ" and "in visu" aspects - precisely because they are meant to be

lived and seen. Landscaping and gardening devices must thus count

with a landscape or a garden (objects), a "landscape" or a "garden"

(pictured); but also with designers with multiple and tiered know-how

(landscaper, gardener, architect, artist, contractor...) who act on

the "seen" as well as on the "experienced"; but also with a spectator

(focusing on the category of "seeing") or a walker (focusing on the

sensitive categories of which "seeing" is only one modality) who sees

and experiences landscapes and gardens.

1

How can we reflect the experience of moving around in a garden without

being present? During a visit, the first image we often have is a global

one: the plan that is given to us at the entrance. This overview

synthesizes the different elements that make up the garden and gives the

main informations. It is a first visit in itself, or a pre-visit. This is

the way the "French gardens" are considered, which

were created on huge areas with a remodeled and flattened ground all

around the houses.

2

This flatness can be explained by their very origin,

a drawing showing the embroidery made on the rich fabrics and laces.

3

The French gardens of the modern period (Art Deco)

tended to be two and a half dimensions rather than real spatial

compositions, [...] compositions that are approached through vision

rather than experience, [...] made in a single moment.

4

Thus applies the first view of our "Web garden".

Kaiyûshiki type garden, or stroll garden, is completely

differently thought out:

it is made in such a way that it cannot be embraced from anywhere at a

single glance. [...] The stroll garden is not a painting in which all

the details can be captured simultaneously; it is like a book whose

pages must be turned successively.

5

The movement of the walkers is thought of as the constituent element.

Landscapes follow one another, appearing and disappearing in the course

of the progression. By taking up the idea of pages, we have multiplied

the points of view, thus isolating each element when you click on it.

Another feature of the stroll garden is its evocative power. [...] The

gardeners did not try to reproduce the sites faithfully; they reduced

the number of elements and schematized the landscape.

6

Our research (photomontages and drawings) has an ambiguous status here.

They are thought of both as autonomous sculptures and as the landscapes they represent.

1

Séminaires Paysage et Jardin : Un Autre Regard Sophie Houdart

2

Les plus beaux jardins de France

3 Ibid.

4

French Visions in the Modern Garden. Dorothée Imbert, quoted in

Reinventing garden sculpture at the 1925 Paris exhibition of

decorative arts

Louis Gevart

5

Les jardins japonais : principes d'aménagement et évolution historique

François Berthier

6 Ibid.

Can we express identities throughout a garden?

During the lockdown, I discovered the magazine "Les jardins du

retour" published by Les Carnets de l'exotisme and the term

"Anglo-Chinese garden" (the French name of the English landscape

garden) . By its name it immediately evokes me an interbreeding

which I could relate to and I ask myself: is it a mixed-race garden?

In their 1750 collection, John and William Halfpenny propose

kiosk projects from all origins to English owners. The Cahiers

from Le Rouge, in 1775, indicate how to structure a garden around

an architectural setting. The

Traité de la composition et de l'ornement des jardins ,

published by Audot, publisher of Le Bon jardinier , proposes

"in more than six hundred figures, plans of gardens, follies for their

decoration and machines to push up the water". Its success was such

that in 1839, it was in its fifth edition. The trend of the

Anglo-Chinese gardens was born, and takes this name after Le Rouge,

engineer and geographer of the King, publisher of many engravings

books, had published in 1774 the twenty-one volumes of the

Jardins anglo-chinois à la mode.

1 Architecture in Anglo-Chinese gardens would thus be

inspired by monuments of all origins?

In a letter addressed in 1754 to her mother, Sophie-Dorothée of

Prussia, Queen Ulrika of Sweden, describes the Chinese pavilion

that the King gave her for her thirty-fourth birthday. Her son,

dressed in Mandarin, reads a poem and hands her the keys to the

pavilion. She then enters the pavilion to discover panels decorated

with pagodas, birds and vases. The sofas are covered with Indian

fabrics and the furniture is made of Japanese lacquer.

2 Chinese, for Japanese or even Indian, the term would

thus rather refer to the "Easterner". Could we see here an origin to

the fact that the entire East Asian population in Europe is perceived

as "Chinese"? Similarly, what is the real interest of the Other through

the creation of gardens and pavilions that look like Chinese pagodas

or Turkish kiosks, of Eastern inspiration (from the south of the

Mediterranean basin to the Far East), when at the same time Buddha is

presented as

the Antichrist, the one who will come before the end of the world,

disguised as Christ, to fill the earth with horrors and heresy. 3

It is particularly interesting to note that Buddhism has always

been a kind of mirror in which Europeans have observed themselves

pretending to believe that they were looking at a distant Asian

religion. This instrumentalization of Buddhism, which usefully

highlights the philosophical and theological quarrels or the social

issues and observations of Europeans, is therefore above all their

most secret anxieties expression. 4

This mirror metaphor also seems to be relevant regarding

the orientalization of gardens:

withdrawing "to The China" [here The China refers to the Chinese

pavilion] for a few hours per day to taste spices and tea enable

to grant oneself the most precious of goods: the freedom to be

oneself, 5

and I do not find in this European-centric interest the idea of

interbreeding that interests me.

It is true that we come to each experience with our own limitations

and see only what we are prepared for.

6

Isamu Noguchi, for the Unesco garden in Paris,

invents a new space adapted to modern architecture, which is at

the same time different from the Japanese garden and from

monumental sculpture. But his work faced with hostile reception,

as experts of traditional Japanese culture did not find it

authentic, and modernist art critics reproached it for not being

original.

7

For example, Pierre Montal criticizes the "false archaism" and

"false exoticism" of the elements shaped by Noguchi in comparison

with natural Japanese stones. John Ely Burchard follows the same

line of criticism: "The older message that Japan so often gives

us, that natural forms are admirable, even when stylized and

artificially manipulated to provide an abstract summary, appears

here, but less convincingly and with less purity than in more

traditional Japanese works, especially those of centuries ago."

8

This desire to have authentically Japanese work

stems from UNESCO's own policy. The presence of an Eastern

culture - in fact non-Western - is necessary to avoid the total

domination of Western arts and artists in the construction site.

9

Critics completely disregard the identity of the artist and

accentuate his "Eastern" origin. In 1933, when the artist proposed

Monument to the plough , an environmental project that he

imagined in the Middle West meadows, he

encountered two major obstacles: the administration refusal, only

possible recourse for creating such a vast work at the time, and

the racial criterion in the reception, especially when it was a

question of creating a monument on such a symbolic land.

10

Art critic Henry McBride wrote

in his review of Noguchi's exhibition at the Marie Harriman

Galleries: "I hate to apply the word "wily" to anyone I so

thoroughly like and respect as I do Mr. Noguchi, yet what other

word can you apply to a semioriental sculptor who proposes to

build in the U.S. the following gigantic monuments. »

11

Isamu Noguchi's example is important to me as the first (or one of

the first) international artistic figure from a "Far East/West"

mix and I see in his garden for UNESCO an attempt to express our

dual identities.

In my case, what would a "Franco-Japanese garden" look like?

1 Des paravents de laque aux jardins anglo-chinois :

l'architecture exotique dans les parcs et jardins Nadine Beauthéac,

Les Jardins du retour, ed. Les Carnets de l'exotisme, p. 39

2. Ibid, p. 33

3 Une figure paradoxale du péril jaune : le Bouddha

Muriel Détrie, Orients Extrèmes, ed. Les Carnets de

l'exotisme, p.73

4Free extracts of

La rencontre du bouddhisme et de l'Occident

Frédéric Lenoir

5 Des paravents de laque aux jardins anglo-chinois :

l'architecture exotique dans les parcs et jardins Nadine

Beauthéac, les Jardins du retour, ed. Les Carnets de

l'exotisme, p. 33

6 Isamu Noguchi quoted in

La création-découverte dans l'art et dans la science.

Jacques Mandelbrojt

7

Japanese Garden in France: Exoticism, Adaptation, Invention

Hiromi Matsugi

8

Isamu Noguchi’s “earthwork”: an Anticipation of Land Art and an

Identity Question

Hiromi Matsugi

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11 Henry McBride, « Attractions in the Galleries », New

York Sun, 2 février 1935, quoted by Isamu Noguchi in Isamu

Noguchi, A Sculptor’s World, Londres, Thames and Hudson, p. 22.

in

Isamu Noguchi’s “earthwork”: an Anticipation of Land Art and an

Identity Question

Hiromi Matsugi

Who would believe, considering today's leprous shores, withered edges,

all this smoky landscape, invaded by construction sites and factories,

that around 1860, in view of Saint-Ouen island, beautiful trees were

growing, offered rich and thick foliage, that it was here - on this

island - that Edouard Manet conceived and created The Luncheon on the

Grass [...]?

1

Paris landscape and its surroundings seems to have changed a lot in a

relatively short period of time. However, the attractivness of lunches

on the grass, or picnics, has not disappeared. On May 16th, a few days

after the end of the lockdown, the Parisien (a french daily newspaper)

titled a video

At bois de Vincennes, the comeback of lunches on the grass.

During an outdoor picnic, we don't only eat food (and besides, it's

often not as good as what we can eat at home), we also consume the

setting that surrounds us. It wouldn't occur to us to picnic where the

setting is ugly. The location is also carefully chosen, not too many

branches or stones or brambles, preferably flat ground and shade to

protect from the sun. Would the decor painted by Manet, corresponding

to this ideal, have defined the criteria for the perfect picnic spot?

The Lunch on the Grass is the largest canvas by Edouard Manet, the one

on that he realized the dream that all painters have: to put life-size

figures in a landscape. ...] What you have to see in the painting is

not Lunch on the Grass, it is the whole landscape, with its strength

and finesse, with its foregrounds so wide and solid and its backgrounds

of such light delicacy; [...] it is this vast, airy whole, this corner

of nature rendered with such a just simplicity, this whole admirable

page in which an artist has put the particular and rare elements that

were in him.

2

Can this dream of immortalizing the human presence in nature be found

today in furniture stores, in advertising messages such as IKEA's:

Bring nature into your home

/

5 ways to invite nature into your bedroom

/ ... These slogans transform the way we see what is in the setting (or in

the room) into a natural space in which we can be.

1

Edmond Pilon. (1939). L’Ile de France. B. Arthaud Editeur. p.38

2

Emile Zola quoted in

Aut pictura, poesis : Baudelaire, Manet, Zola : Nicole Savy

Artificial grass is increasingly replacing lawns, especially in

sports fields such as tennis or football. The main interest is

economic.

While it costs around 20,000 Swiss francs per year to maintain

an artificial surface, the natural grass surface costs more than

twice as much. In addition, the natural surface has a service life

of 10 to 15 years, depending on the model, while the natural

surface has to be changed several times during the season.

1 The visual illusion is becoming more and more perfect,

but effects on players' health can be felt.

Specialists such as Dr. Gérald Gremion, head of the Swiss Olympic

Medical Center in Lausanne, confirm the danger. "The absorption

capacity of this type of surface is less, which increases the

risk of aches, sprains or torn ligaments," he warns.

In just a few years, the impression made by artificial lawn has

improved considerably.

In 2004, the team of the Jeunesse Esch in Luxembourg received a

magnificent artificial lawn the day before ... which the gardener

had mowed the day after its delivery. ...] Cut to the ground, the

artificial grass had then suffered serious damage, even before

being unable to host a single match.

I see in this gardener's gesture the desire to go beyond the visual

aspect of imitation. Looking is no longer enough, by behaving with

an artificial grass in the same way as with a vegetable one, the

gardener wanted to animate it. Shouldn't we think, as the next

improvement for artificial lawns, to make them grow?

I mowed a line in an artificial grass to pay homage to this

gardener, and to perfect the illusion, hoping to see it grow again.

1

La controverse du gazon artificiel Marc Allgöver

2 Idib.

3

Le jardinier tond la pelouse synthétique du stade, une boulette à

800 000 euros

Fred

This sculpture project originates from a souvenir of my visit in

January 2020 of the Koishikawa Kōrakuen, a garden located in Tokyo.

Many comments found on the internet praise the beauty of this site

in autumn, when the leaves blush and blend with the red of the bridge,

or in spring when the weeping cherry tree on the banks of Osensui

, the main lake, is in bloom. During my visit, although open to

the public, the garden is under construction and I witness another

spectacle, that of creation, or rather of maintenance, that of the

machines and beings that repair.

When I visit a garden, I often forget the underlying construction

work, or more precisely, I don't think about it. The illusion of

naturalness is perfect, yet the grading, the leveling, the

installation of ponds and electrical systems, everything is

artificial. Terms such as "landscape construction" and "landscape

mason" make an obvious link between building site and nature.

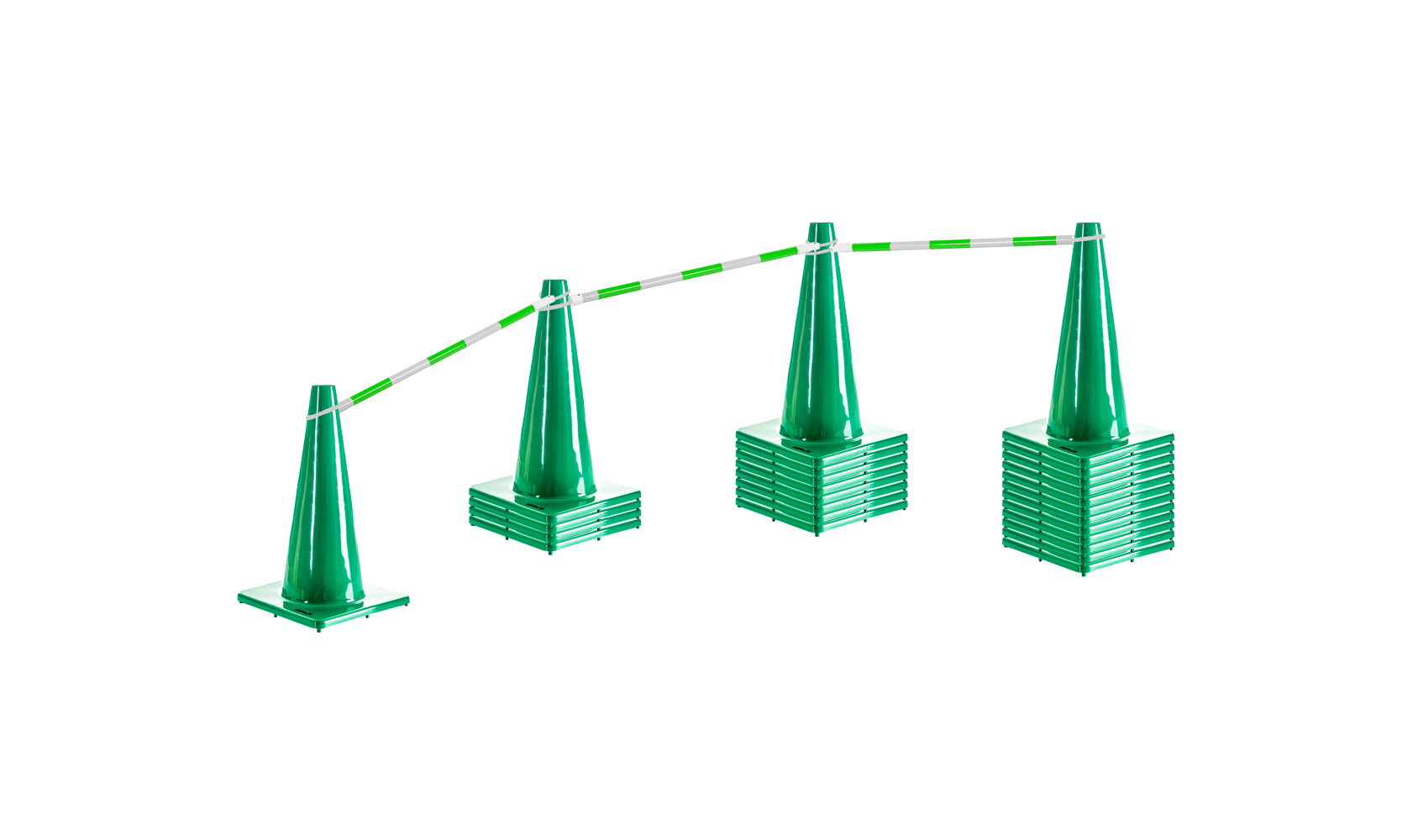

Before arriving at the tsutenkyo (the red bridge) I take a

staircase that climbs up a hill. A guardrail made of green

construction cone assembled by stringers is temporarily installed.

The sculpture I imagine takes up this configuration, but in the

absence of steps, I superimpose the cones to represent the slope.

Studying the mimicry of his chameleon raised in freedom in his

studio and the colours to be used, the artist

[Louis Guingot]

arbitrarily chose three basic colours borrowed from nature and the

garden:

— A meadow green: this is the dominant colour, resulting from a

mixture of several greens visible in nature and according to the

season: the colour of the grass, the leaves of the vegetables in

the garden and the trees.

— Red-brown: this is a

colour that reflects the local soil of Lorraine, a colour that Louis

Guingot saw daily in his garden and in the surrounding fields.

Probably, he was also inspired by the reddish-brown mosses hanging

on stone walls and the edges of garden paths.

— A dark blue:

commonly known as "the Guingot blue", it is a particular blue that

only the artist knew the secret of its manufacture and that he used

commonly in his theatre sets, to partially underline shadows,

branches, trees... 1

It was in 1914, at the beginning of the conflict with Germany, that

Louis Guingot, together with Eugène Corbin, director of the Magasins

Réunis, created a camouflage jacket for the French army soldiers,

still wearing the madder red trousers of 1870. The two men wanted to

offer an alternative to this uniform, which exposes the French

infantryman to all dangers. Eugène Corbin supplied Louis Guingot with

a canvas jacket made in his Nancy workshops. On this jacket, Louis

Guingot drew inspiration from the work of the Impressionist painters

and the Pointillists to create the motifs intended to hide the troops

in the surrounding landscape.

2

Would military camouflage have been possible

without Impressionism, and without

the emergence in our midst of Japanese albums and images

[that]

completed the transformation, introducing us to an absolutely new

colouring system

3? Art and its exchanges modifying our perceptions, how

would this jacket have been painted in another artistic context, a

few decades earlier? Or later? Rather than hiding the artillery pieces

under large canvases painted in the colours of the surrounding nature,

would the soldiers have hidden them under Didier Marcel's

earth-coloured "Labours"?

In the regular French-manner gardens, inspired by the sculptures of

Roman Antiquity, the statue became

the most prized ornament among the creators and theorists of

garden art of the Louis XIV era

4. As a reminder of those human representations, I placed

a mannequin in the middle of the garden. Present (or absent) for too

long, ivy has grown on its immobile body. Great reader of

Romanticism, the gardener made plant masks to cover its mouth and

nose, in prevention of the COVID-19 pandemic.

1

« La première veste de camouflage de guerre du monde » est

inventée par Louis Guingot Frédéric Thiery

2

Musée Lorain Website

3Duret Théodore, 1885, Critique d’avant-garde, p.

98. quoted by Michael Lucken in Les Fleurs artificielles

4

Reinventing garden sculpture at the 1925 Paris exhibition of

decorative arts Louis Gevart

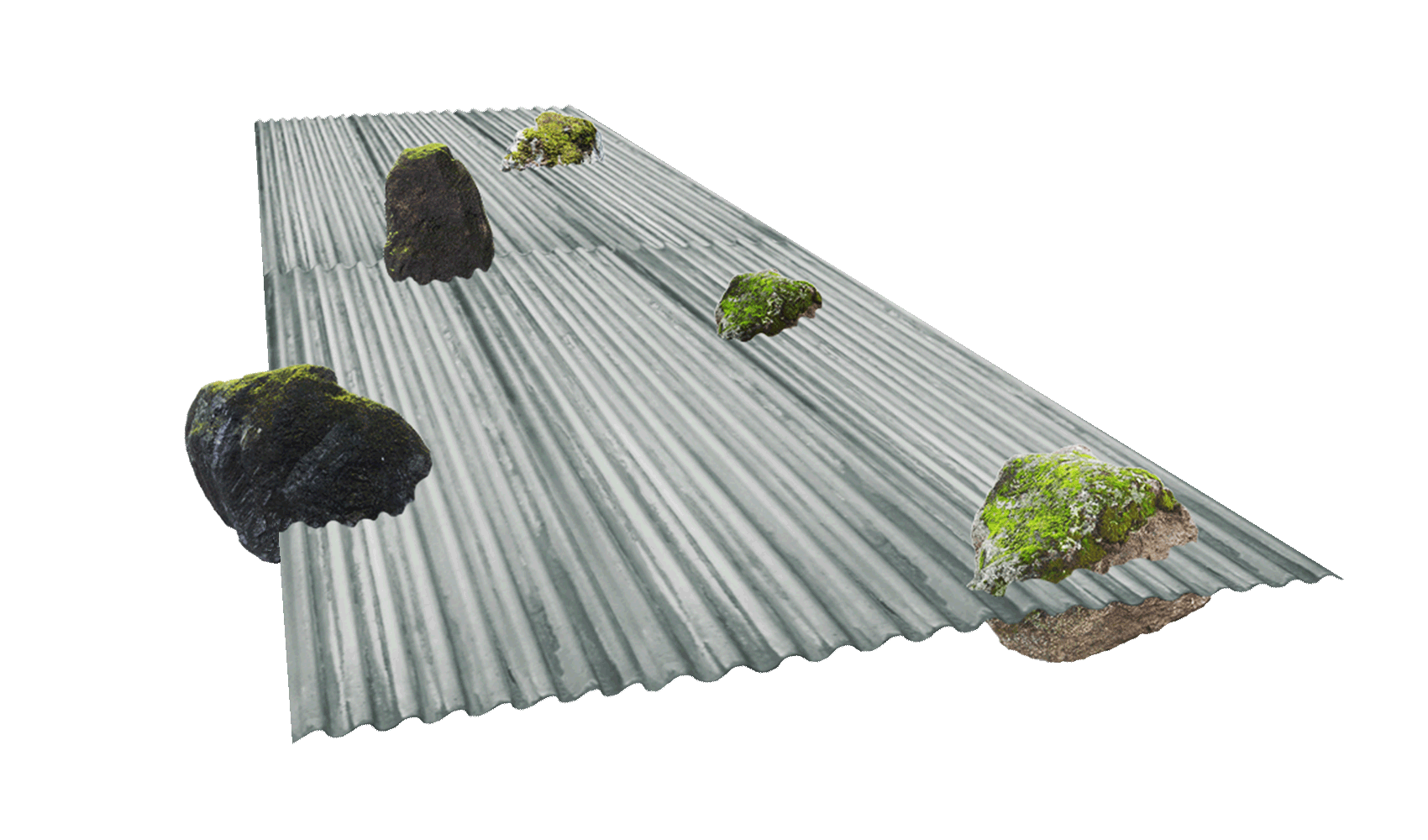

By autumn, the leaves turn yellow and red and conifers appear in the middle of the deciduous trees of mixed forests. They can be distinguished until spring. The idea that these two types of trees can be represented by the same object is quite beautiful: a green parasol unfolded or folded up. And under their shadows I find the freshness of the undergrowth. This photomontage is the only one made before the residence, probably to remind us that the trees grew somewhere else before being moved to the garden space.

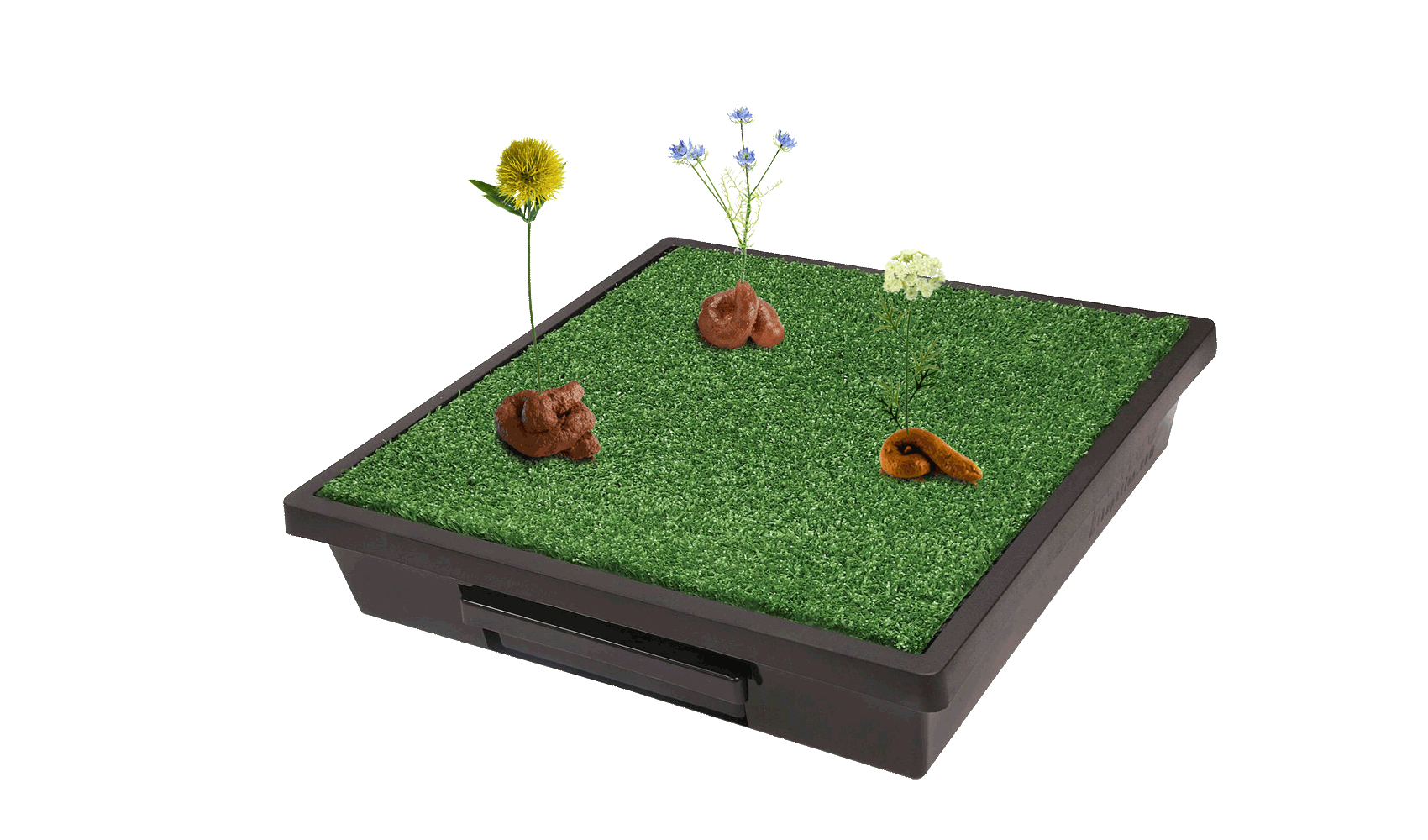

Like all public squares, the Place Saint Léger is populated by

small and large dog droppings. It can be seen as a park of anonymous

sculptures paying homage to bourgeois cuisine because according to

my research, in small towns, most dogs turn their tails at canigou

[French brand of dog food] and other cans.

1

It was the same on the square overlooking my studio in Monflanquin.

Each day brought its new cases. Thinking back to the project for the

Place Saint Léger in Chambery proposed by the artist Erik Dietman (to

install bronze full-scale dog excrement sculptures instead of the real

ones), I think I could have thought of something to change the status

of these excrement. As soon as the first wild flowers appeared, I

could have picked some to plant in the droppings and we would have

said to ourselves: "Oh, today there are still plenty of new flowers,

how beautiful nature is...". " rather than getting angry at nameless

dogs. Considering their number, the square would have quickly turned

into a small garden.

If one is rather fond of flowers inside the house, one can replicate

this process with artificial grass litter.

"ANYTHING THAT CASTS A SHADOW IS SCULPTURE, EVEN DOG SHIT........................................."

1 Erik Dietman on

Agency of Unrealised Projects

Website

2 Ibid

In an Auchan supermarket, while shopping, I am astonished by the name of a water: Orée du bois (Edge of the wood) (6X1L). Its romantic name makes me want to go outside, and as Titeshuya remarks in his·her review left on Auchan website the format is convenient, perfect to take everywhere. So I take it in my bag for a walk in the forest and discover at the edge of a wood a pond covered with tiny green floating plants, whose stagnant water full of mosquito larvae seems to correspond more precisely to its name than the clear water. I fill my now empty bottle with it and repeat the process the following days for the whole pack. I take care to draw the same volume of pond water from each of them, and once put together on the table, the green surface reproduces visually through the plastic walls. I wonder how many bottles will be needed to reconstitute the whole pond.

To tame places, peoples, practices and ideas that are strange and

foreign implies that they should be detached, at least partially,

from their particular roots. Appadurai (1986: 28) evokes in that

respect an "aesthetics of de-contextualization" by taking as an

example the misappropriation of sacred objects or tools from

distant countries that are marketed, consumed and exhibited in

European and North American homes. In religious exoticism, we will

find such a process of de-contextualization and provision where

[...] these are presented as practical methods of accessing

well-being and self-realization - which, of course, makes them

familiar and predictable. 1

In DIY and garden stores, many orientalizing articles are offered

for sale. Mainly of Buddhist inspiration, these objects praise the

possibility of a calm, meditative space, a "Zen" bubble in our

swarming and noisy modernity. I typed " Buddha " in the search bar

of different websites (Leroy Merlin, Point P, Jardiland...), and I

always get something to buy. I can classify the different Buddhas

from A to Z, by increasing or decreasing price.

The ambivalence of the desire to recharge one's batteries with

so-called oriental religions, which one would like to adjust to the

Euro-American societies values and lifestyles (because they are too

austere, too "fanatical" and, implicitly, too "oriental") is a

result of a religious exoticism. This exoticism implies an

idealization of traditions that are foreign to us as primordial,

mystical and authentic entities and also reveals a deep ambivalence.

Fascination coexists with a more or less pronounced discomfort with

strange and distant traditions, making it necessary to tame them.

2

This taming is explicit in these stores. Often staged in quasi-parodic configurations, buyers can appropriate these objects by transposing them

by imagination into their own garden then by buying them. We make it a

trend.

Giving your exterior the look of a Zen garden is in vogue today. The

use of elements such as Japanese footsteps makes possible to create

pure spaces where the aim is to walk as well as to recharge one's

batteries.3

A garden is above all for walking. Japanese footsteps build the idea

of a path and materialize the contact points between our body and the

ground.

What is beautiful in a garden is not each element but the

relationship between the elements. What is even more important is

that there is space, human and time. A human has to walk in it with

his feet to discover it.4 Here, the path

has been shaped for an aesthetic effect, with stones so-called, in

garden art, "crossing stones", watari ishi 渡り石 (often

translated as "Japanese footsteps"). They are used in particular in

the tea garden, roji 露地. Their name literally means "stones" (ishi 石)

for "crossing" (wataru 渡る). To cross what? The garden, apparently, to

the tea house (chashitsu 茶室). [...] Besides walking, there is

obviously also some scenery, or decoration; but that's not all yet.

The word that means "to cross", wataru 渡る, is written with a sinogram

with water radical on its left, in the form of three drops. This is

because, in fact, the original idea was to cross a river, or more

precisely a mountain stream, by jumping from stone to stone. 5

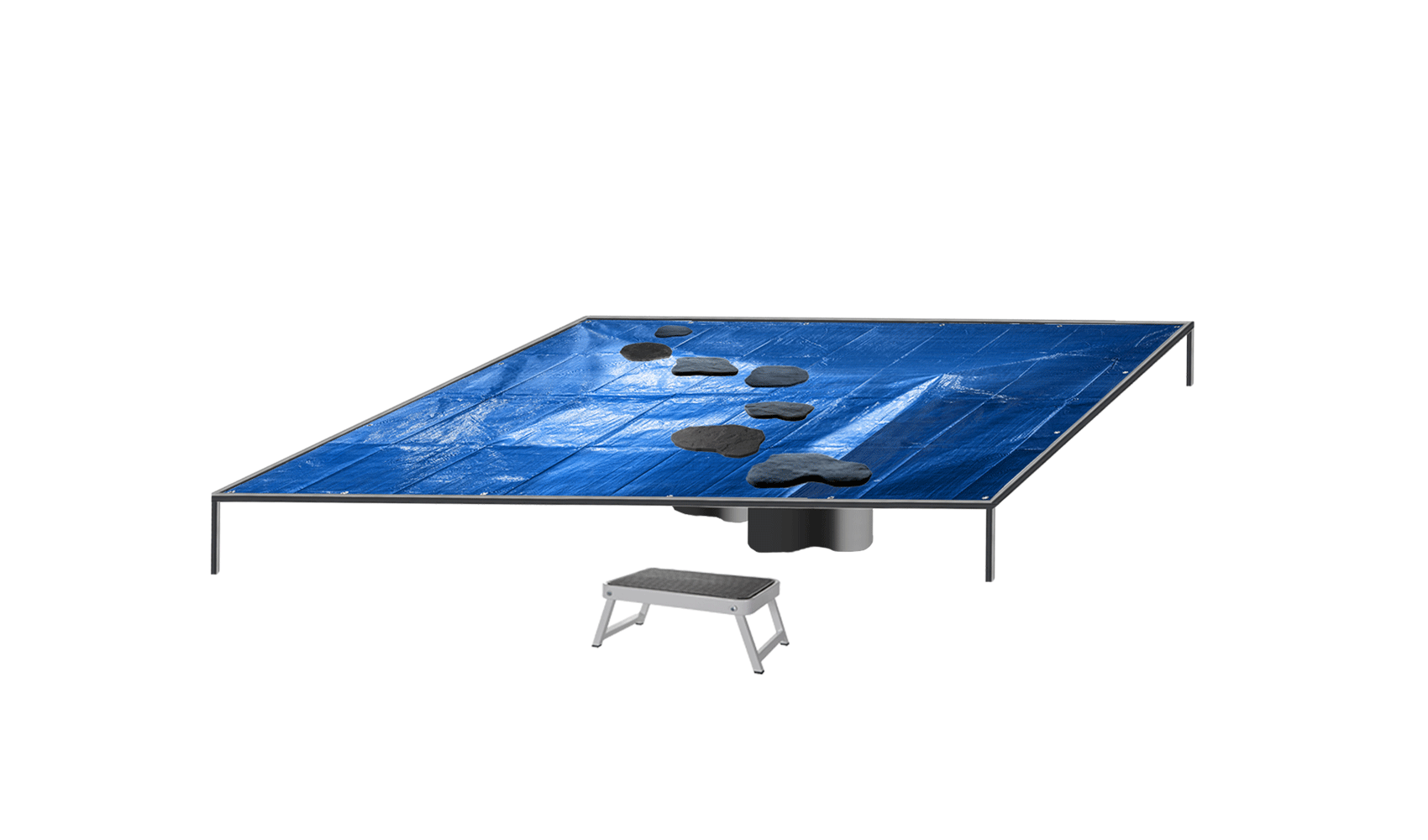

This sculpture is designed to be crossed. A path of flat stones

(Japanese footsteps) is used to cross the space. The stretched blue

construction tarpaulin is a memory of my Koishikawa Kōrakuen visit,

the oldest garden in Tokyo. When I went to visit it in January, the

garden was under renovation. A large tarpaulin was covering a trench

dug in the earth, a river in the making. In the sculpture, the tarp is

a bit raised to evoke "the risk" of slipping off the stone and falling

into the water.

1

Religious Exoticism and Hybridity Véronique Altglas

2 Idib.

3

Point.P Website

4 Isamu Noguchi quoted in

Isamu Noguchi’s “earthwork”: an Anticipation of Land Art and an

Identity Question Hiromi Matsugi

5

The Walking to Japan Augustin Berque

Fall here refers directly to the waterfall. A garden

is said to be cursive (gyô)

if the emphasis is put on symbolic designs (an upright stone

suggesting a waterfall) 1. Here, it is not a stone but a transparent shower

curtain that represents the waterfall. In both cases, stone and

curtain, the water is suggested by the element against which it

flows. It is made visible by its absence. The preformed black plastic

pond is used to install a small water feature in a garden. Buried,

its outline is often hidden by cleverly placed stones. Small

compartments on the inside edges of the basin usually accommodate

water plants.To perfect the layout of my pond, I added lotus flowers

found at the supermarket: a roll of Lotus brand toilet paper and

Tahiti shower gel "under a tropical waterfall", with lotus flowers.

A few kilometers from Monflanquin is the Latour-Marliac water

lily and lotus nursery. Unfortunately, as I left because of the

lockdown on March 15th, I could not visit it, as the opening to

the public starts every year on April 15th. However, I realize that

I have already seen part of its production in Giverny, in Claude

Monet's Jardin d'eau.

Once the Giverny pond was finished, Claude Monet ordered a large

quantity of water lilies from Latour-Marliac; the order forms are

still in our archives. These are the same water lilies that were to

become the subject of his famous paintings, the Water Lilies, now

on display at the Musée de l'Orangerie in Paris. It is surprising to

note that in the historical works relating to Claude Monet's most

famous paintings, there is little or no mention at all of

Latour-Marliac's role in their creation. It is arguable, however,

that Claude Monet painted more than just pretty flowers - he managed

to capture a botanical innovation on canvas and his paintings are

among the earliest mentions of non-white water lilies growing in

Europe.

2

1

Les jardins japonais : principes d'aménagement et évolution

historique François Berthier

2

Latour-Marliac

Website

Bamboo became an object of exoticism as soon as it arrived in France,

when Eugène Mazel created the Prafrance bamboo plantation,

a small China 1 as he so aptly describes it. While

stacking glasses at home, I am surprised by the formal and structural

analogy between my stack and a bamboo culm: the bottom of the glasses

is as full as a node and the body is hollow.

1 La bambouseraie Prafrance, Eugène Mazel, le rêve prend

corps. Jeanine Galzin in Les jardins du retour, ed. Les

Carnets de l'exotisme, p.80

Can we walk around a supermarket? Or rather, can we think of the

supermarket as a place for strolling or philosophy? While shopping,

in the middle of the shower gel and shampoo aisle, I imagine myself

in a tropical greenhouse. Here I am surrounded by a collection of

products in many bright and eternal colours, with contained, secret

and inaccessible smells, except when I get closer and open the lid.

And some labels indicate me the name of these flowers and give me

some information about their attributes. I learn, for example, that

coconut water is

well-known for its moisturizing properties1 and

that orange blossom,

this elegant white flower is harvested between April and May after

the dew has lifted 2, on the labels of Le Petit Marseillais' Coconut water

and orange blossom moisturizing shampoo.

If hypermarket is a garden, it is time to specify that it is

rather a "greenhouse" (Note that the figure of the greenhouse here

is much more than a metaphor, as Dominique Desjeux [2003] shows

when he reminds us that department stores and large tropical

greenhouses in Paris, Copenhagen or Kew Gardens in London were

made possible by the mobilization of the same architecture of

glass and steel), and moreover, an opaque greenhouse, a

storehouse. However, in the storehouse, three types of windows

have been cut out, often independently of the gardener, but also

in spite of him, or even on his initiative, all symptomatically

open towards the environment - towards the city and/or towards

nature.3

Taking this remark at face value, this window opening towards

nature is perceptible on these same labels. The words nature or

natural are omnipresent. This window opens up in the imagination

of consumers. The evoked nature sells and transforms the shower

into a sensory experience.

When pleasure comes into play, the effectiveness of the product

against dirt is no longer the only determinant of this choice at

the purchase time, but a multitude of other parameters appear,

such as the smell - and what it implies as an effect on the

"shower experience" -, the aesthetics of the packaging or the

characterization of the moment itself as pleasure, relaxation or revitalization. Indeed, "the consumer does not consume the

products but, on the contrary, consumes the meaning of these

products, their image. That the object fulfils certain functions

is taken for granted by the consumer: it is the image that makes

the difference" (Cova et Cova, 2004, p. 201).4 Could it also be the image that makes nature?

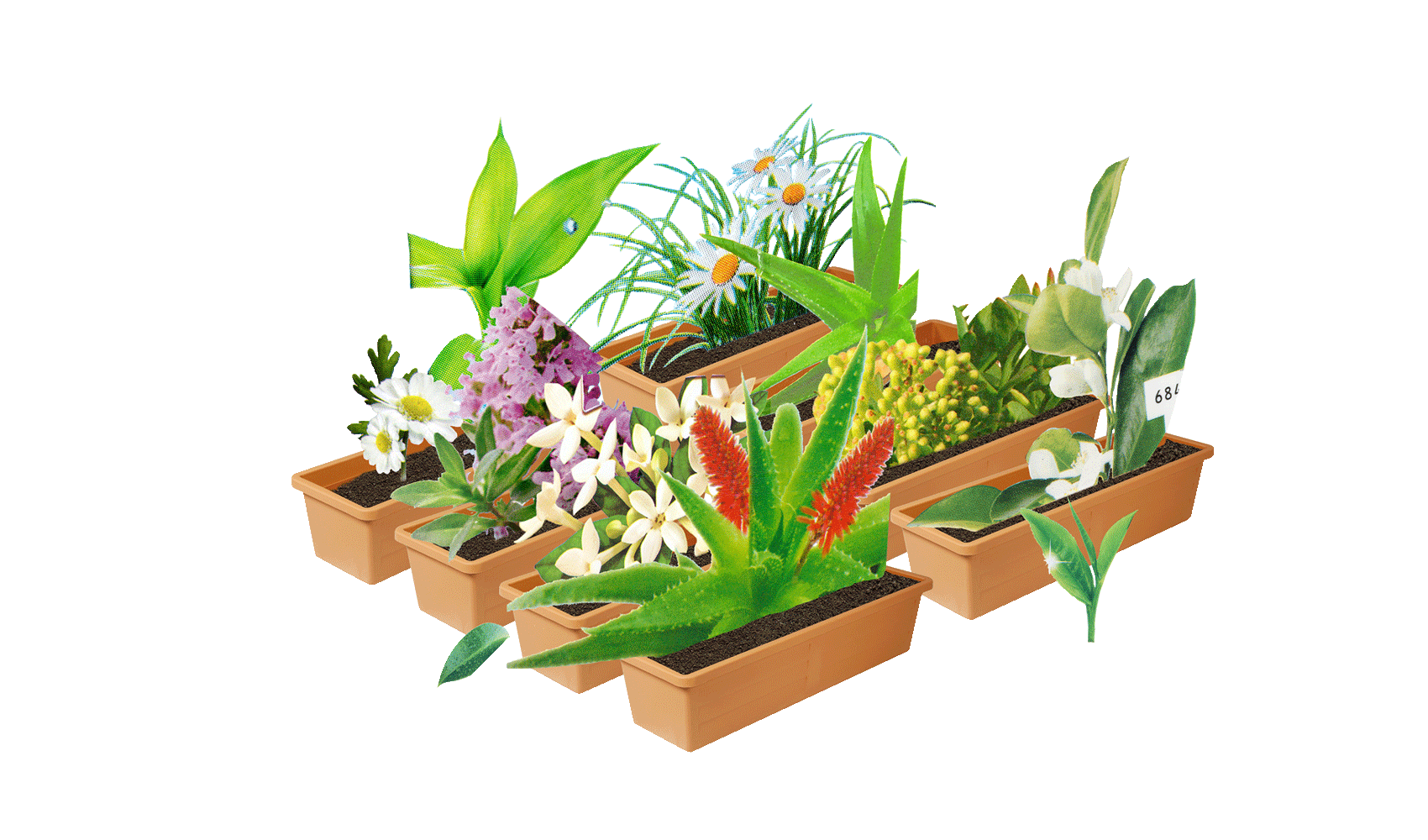

I went to Monflanquin's Casino supermarket to collect flowers

and plants from shower gels or shampoos bottles labels. During

the lockdown, I was able to continue my picking in Burgundy at

Avallon and Clamecy's Auchan supermarkets. As supermarkets were

the only areas still open, I wondered even more seriously whether

these areas could be considered as places to stroll around. Only

official excuse to move around, some of my friends couple separated

by the lockdown sometimes went there to meet for a few moments.

With the idea of reshaping a garden from these nature images, I

planted them in soil and combined them with gardening specific

elements.

1

Petit Marseillais

Website

2 Ibid.

3

The Superstore: Another Type of Garden at the Doors of the City Franck Cochoy

4

An Economic Construct? Consumer Products and Gender Differentiation.

The Case of Shower Gels, Isabelle Jonveaux

SANNOLIK Vase, pink, 17 cm, 5€

BLANDA BLANK Serving bowl, stainless steel, 20 cm, 4 €

TROLLBERGET Active sit/stand support, Glose black, 89 €

FEJKA Artificial plant, in/outdoor, Box ball shaped, 35 cm, 23 €

TINGBY Side table on castors, white, 50x50 cm, 29 €

Total height: approx. 142 cm

Total price: 150 €

I chose objects at IKEA store for their shape: cube, sphere, pyramid,

hemisphere and a drop shape (or a jewel shape). They symbolize

respectively earth, water, fire, wind and the void and together

form the five Japanese elements:

godai .

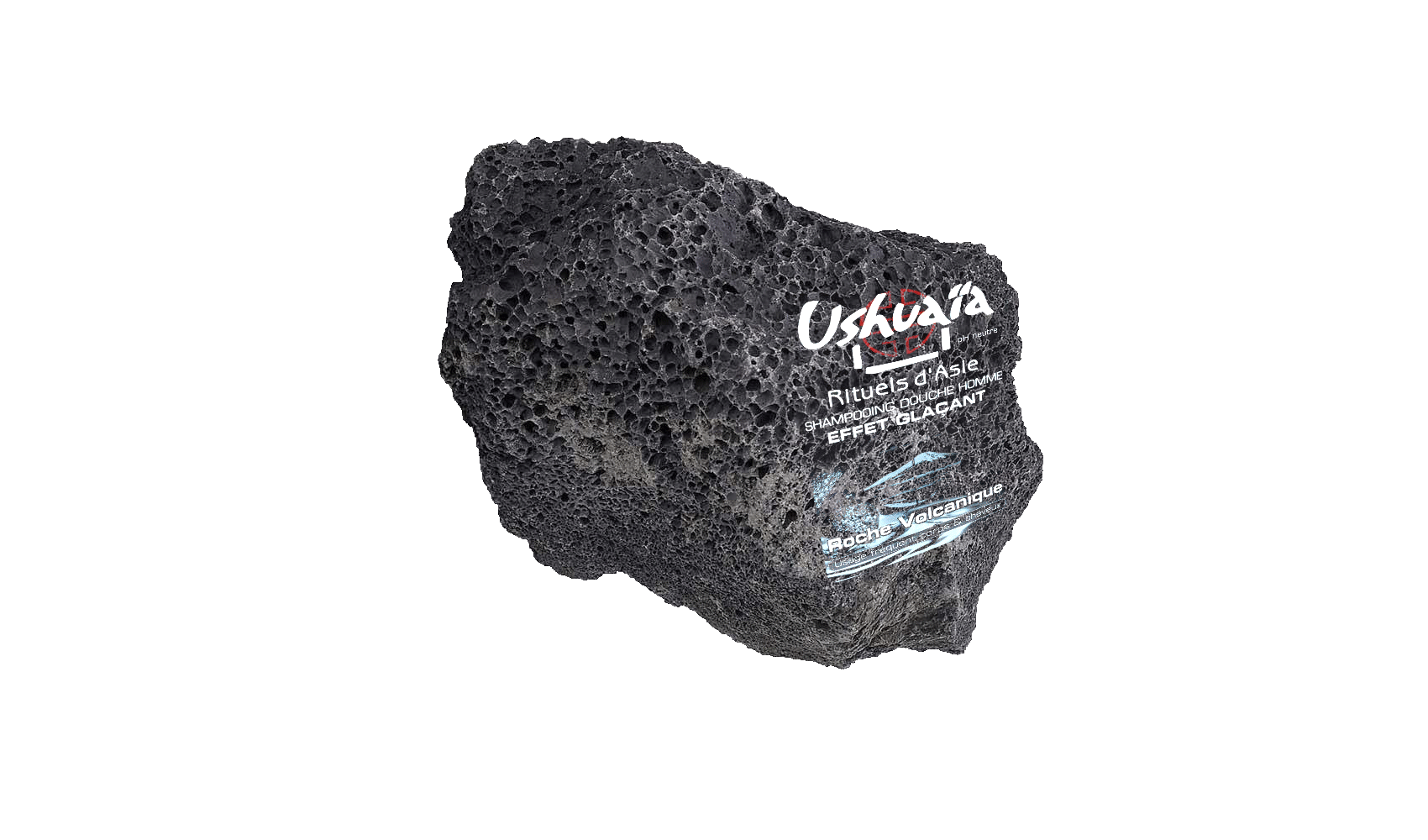

In Asia, warriors pass on rituals that stimulate body and mind,

the secret of their physical and mental well-being from generation

to generation. Ushuaïa restores these ancestral rituals to you in

its new Ushuaïa Rituals of Asia shower gels for men. Ushuaïa

Research has selected volcanic rock and combined it with refreshing

natural menthol, giving the skin a cooling effect that awakens the

whole body.1

This description on the back of the bottle of Ushuaia's Rituals

of Asia shower gel stumps me. Which warriors are these? I suppose the

Mount Fuji printed on the front of the bottle must direct us to Japan,

but why be so evasive? Asia is huge. Much more than the area defined by

a circle surrounding ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) by

Ushuaia. Looking at this product's reviews, a customer comment confirms

that we are talking about samurai here.

A shower door that opens, a dose of gel in your hand, you close your

eyes, and you find yourself propelled to Hakone at the beginning of

Meiji era. I feel the rough breath of the samurais around me and in

the distance the banner of the Shogun. The fight begins, the sabre

blows, spurts out and causes sparks that spurt out flames on the dry

twigs on the edge of the lake. The volcano rumbles, the atmosphere

becomes heavy and sulphurous, the temperature rises as volcanic ashes

gush out. The sakuras are crying from this spectacle that is about

to happen, the ronin goes back to its den, the men separate, I return

to Kanazawa. I open my eyes, I have travelled and I smell good.2

This caricatured comment, in addition to being historically false

(there is no longer a shogun at Meiji era), shows an experience solely

triggered by the packaging exoticism. The shower gel fragrances (namely

volcanic rock and menthol) in themselves cannot develop imagination in

this way.

It is no longer just a question of becoming clean, but of a

multi-sensory experience acting on body and mind, as [also] the

Palmolive commercial promoting a "wellness shower for body and mind",

with the image of a woman in an oriental meditation position.3

"The Japanese experience" is increasingly offered in shower gels and

shampoos, but also in washing up liquids and detergents. The fragrant

window through which we are invited to enter is the cherry blossom,

frequently coupled with lotus or green tea. Through the figure of Japan,

and more generally the East, far from a real interest in anOther

culture, personal benefits for our bodies are almost always sought:

soothing, relaxation or martial energy, a set of exotic clichés that

the Western world continues to impose.

Exoticism is the product of the discourse on a relationship. Yet, as

Claude Raffestin notes, "every relationship is the place where power

emerges" (1979:46). (1979:46) Exoticism is thus based on power

relations. Raphaël Confiant, a Martinican writer, makes an enlightening

comment on these relationships: "neither the coconut tree nor the white

sandy beach are exotic in my daily life, but as soon as I use the

French language to evoke them, I literally find myself taken hostage,

terrorized in the etymological sense of the term by the reifying gaze

of the West" (quoted by Schon, 2003: 16).4

The primary function of the product is thus almost obscured behind

its secondary functions: who today asks the question of whether one

shower gel washes well, or better than another?5

1

Rituels d’Asie

on Amazon Website

2

Customer review of Rituels d’Asie

on Amazon Website

3

An Economic Construct? Consumer Products and Gender Differentiation.

The Case of Shower Gels Isabelle Jonveaux

4

L’Occident peut-il être exotique ? De la possibilité d'un

exotisme inversé Lionel Gauthier

5

An Economic Construct? Consumer Products and Gender Differentiation.

The Case of Shower Gels Isabelle Jonveaux